Sheep scab on common grazings

Sheep scab is a highly contagious disease with serious animal welfare implications and significant economic costs. It is therefore essential that all sheep put on common grazings are free from scab and are regularly checked for ectoparasites. This page will take you through the steps for how to diagnose, prevent and treat scab

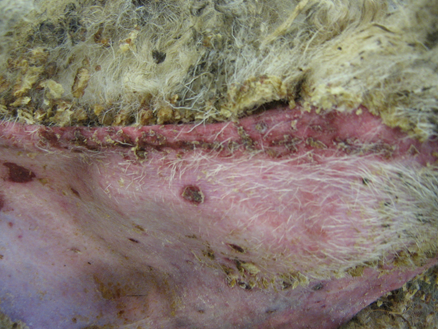

Sheep scab is caused by the mite Psoroptes ovis which feeds on the surface of the skin. This results in an allergic reaction of the skin which causes the formation of scabs under which the mites live. The whole life cycle takes place on the sheep and a mite can develop from an egg to an egg laying adult within two weeks. Mites are typically transmitted directly from sheep to sheep. Adult mites however can survive for over two weeks in wool caught in bushes or on fence posts as well as handling facilities and equipment.

Mites thrive under high humidity and amongst densely stocked sheep for which reason disease outbreaks are most common during winter though scab can strike all year round.

Typically many sheep in a flock are affected showing itchiness and shedding of the fleece. Affected sheep lose condition and may die. On the other hand if the weather is dry and sheep are well fed clinical signs will be less obvious and infested animals more difficult to spot.

How to diagnose sheep scab

Sheep scab can be diagnosed by microscopy on skin scrapes and by tests on blood samples. Skin scrapes or wool plucks should be taken from the edge of lesions and include scabs. This test is sponsored by Scottish Government, visit their webpage on it for more details. Please note that wool samples without scabs or crusts attached to hair roots are of no use for scab diagnostics.

Early signs of scab are subtle and carrier animals may be perfectly healthy for which reason blood testing should be considered for purchased sheep. To get a reliable result, blood from 12 animals per management group should be collected one month after they had last contact with other sheep. A positive result indicates exposure to sheep scab but because the test looks for antibody rather than the mite itself the test does not confirm current infection. On the other hand, a negative result will allow the conclusion that an animal has been free from sheep scab for several months.

How to prevent scab

Sheep scab is mainly transmitted from animal to animal. Introducing clinically healthy carrier animals therefore presents the highest risk for disease incursion. New stock should be carefully sourced and quarantine procedures adhered to; continued vigilance will ensure that scab is detected early.

Scab can also be transmitted indirectly and you should insist that, for example, vehicles and shearing equipment are properly cleaned and disinfected prior to use.

Other common ectoparasites like lice, ticks and flies can also have animal health and welfare implications; preventive treatment therefore has a place where sheep can be gathered on a regular basis.

Common grazing poses a biosecurity risk and treatment of all sheep going to a common grazing helps to reduce the spread of scab. Repeated blanket treatments however have a range of negative consequences and in some cases may not be required. Treating only those flocks where a representative sample tests positive by ELISA will reduce time and costs for treatment. A study in Switzerland involving flocks heading for common alpine pastures showed that targeted treatment based on ELISA results helped to reduce the number of infested flocks over time, whilst simultaneously reducing the amount of chemicals used for treatment. Such approach will help to preserve the effectiveness of drugs and reduce the risks some of the toxic products used pose to people, animals and the environment.

How to treat scab

Sheep scab is a notifiable disease under the Sheep Scab (Scotland) order 2010. Anybody who knows or suspects that sheep have sheep scab must notify the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA).

Automatic movement restrictions remain in force until

- 16 days after treatment unless a product which provides at least 16 days’ residual protection against reinfestation has been used

or - all affected sheep on the premises have been slaughtered and any affected carcases have been disposed of

or - disease has been ruled out by a veterinary surgeon.

Keepers must complete a declaration and return it to APHA confirming their actions.

Early detection is key to reduce the impact of an outbreak. Affected sheep will rub against fence posts and bite at flanks. These signs however are not specific for sheep scab and an accurate diagnosis is essential. Not all sheep in the affected flock will show clinical signs but all contact animals must be treated.

Sheep scab can be treated with plunge dips and injections. Dipping with organophosphate is highly effective against a range of ectoparasites. Purchase, use and disposal of dips however are controlled by legislation and treatment should be carried out in line with the ‘Sheep Dipping Code of Practice for Farmers, Crofters and Contractors’.

Treatment with macrocylic lactones presents an alternative treatment option, in particular for small flocks or flocks with no access to trained staff and specialist equipment. Please remember to weigh the heaviest sheep to calculate the correct dosage and regularly change the needle to reduce the risk of spreading infectious diseases like maedi visna and border disease.

Please discuss treatment options with your veterinary surgeon to ensure the most effective treatment product is used.

Where sheep scab is suspected on common grazing and owners are unable to respond appropriately Local Authorities may get involved. The Order includes provisions for local authorities to clear common grazings and impose movement restrictions. Sheep treated with a product that provides residual protection against sheep scab for at least 16 days may return to a cleared common sooner than sheep treated with other products.

What if treatment does not work

Resistance to injectable products (macrocyclic lactones or MLs) has been confirmed in sheep scab. If sheep continue to be itchy after treatment contact your veterinary surgeon to investigate potential treatment failure. Please note that macrocyclic lactones don’t kill mites immediately. Furthermore dead mites and their faeces remain in contact with the skin and sheep may show clinical signs for weeks after successful treatment.

For further information, read this technical note from SAC Consulting.

For further advice visit our advice and grants page for details of our helpline who will be able to give you bespoke advice to support you and your business.

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service