New Entrants Case Study: Mix of Farming Arrangements

5 April 2018Case Study: Ian McKnight

To build a viable farming business, one young farmer retains flexibility to work within different agreements.

After studying Agriculture at the Scottish Agricultural College, Auchincruive (Ayr) Ian McKnight travelled and worked on dry stock farms in Australia and New Zealand to gain a different perspective and valuable experience. After a short spell in full-time employment, on his return home, it was not long before he wanted to get back to more hands-on practical farming.

“My father was a tenant hill farmer in Wigtownshire. That is the countryside I know best and where I had the greatest farming contacts. That [local knowledge, experience and contacts] was hugely important as the farm was not itself viable.”

Ian become a self-employed agricultural contractor on different farms in the local area, which he found great experience and enjoyable. However, it was difficult to grow his own farming aspirations whilst working long and tough hours.

“I felt their were opportunities locally if I was in a position to react to them.”

Building-up a small flock of pedigree sheep was a first step.

Present day

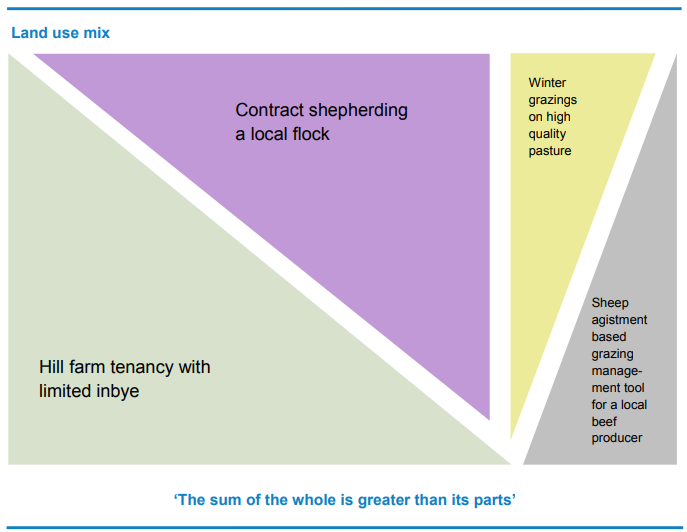

Ian is now working along with several farm owners, using different agreements to flex with their own situations.

“I mould sheep management around what the land owner wants. Provided I have a balance of agreements throughout the year I can optimise output” explains Ian.

Ian gained a foothold onto the farming ladder when he inherited a traditional tenancy from his retiring uncle. It was a hill farm covering 1,600 acres, which was an excellent opportunity that is open to few aspiring farmers. Nonetheless, despite having managed to increase stocking capacity to 500 Scottish Blackface ewes on the unit, the potential income from resulting lamb sales meant it was not an end in itself.

He had to have the drive and skills to make a good job, otherwise he would not have the cash or have been considered to take on further opportunities:

Each land management arrangement has been ‘dovetailed’ into the system. Crucially this allowed the business to grow. This could not be achieved without a flexible approach, understanding of landowner objectives and maintaining good relationships.

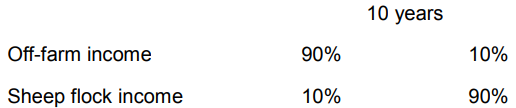

Neither did it happen overnight –

Ian will lamb 1,500 ewes this spring with only limited assistance at lambing. Ian says that “labour is strained at peak times but that is another reason to have enough size to justify additional labour when needed. Many jobs could be carried out quicker with two people meaning the system could be more efficient if simplified and expanded further to justify calling upon someone else more regularly.

Biggest challenges and opportunities

Ian’s Scottish Blackface ewes running on the hill, which is a mix of Molina grass, heather heath and blanket bog.

Ian quickly recounts his biggest challenge has been cashflow with such seasonal income from lamb sales. “It is something we are still working on, that and competing for land with dairy or more established farms is difficult” says Ian.

Calculating what seasonal grazing is worth if it means I can rear more twins is an art, and still depends on a budgeted lamb price or the weather.

We are always fighting against liver fluke and worms, so a vet health plan is important too.

He concludes “I hope some of these difficulties can be seen as a positive – determination – especially by existing landowners who maybe do not want to sell but are thinking of scaling back and recognise that I am trying to build. Hopefully I am doing a good job by those I have an agreement with already.”

Top tips for understanding the best grazing agreement for owner and contractor

- Take time to think about what you want to achieve.

- Keep an open mind.

- Talk to others about the pro’s and con’s of different agreements.

- Have trust and a good understanding of the landowner/farmer and contractor/grazier intentions.

- A written agreement – it structures and encapsulates terms and conditions for the benefit of both parties.

How Contract Shepherding Works

The contractor may or may not have full autonomy over breeding and management decisions but is likely to be responsible for cost control, flock health and livestock recordkeeping together with the day-to-day running of the flock. Depending on the personalities involved and their relationship, frequency of communication and levels of oversite will vary.

The contractor either requests purchases, such as medicines, or claims them back through regular invoicing.

In return, a labour (and any bike/dog) charge is agreed per ewe to be paid at agreed intervals. This would typically be monthly or quarterly which can also coincide with main farm income/sales. Incentive bonuses can be built into the agreement for e.g. lambs reared.

It is a relatively simple arrangement but like any ‘partnership’ it does require trust and familiarity with mutual understanding of respective responsibilities and aspirations.

It is unlike a contract farming agreement, where contractual charges exist between farmer and contractor plus division of any profit.

Through a separate agreement, either party within a contract farming agreement could own the flock. The contractor does not own the livestock within a contract shepherding agreement.

How Agistment Works

Grazing sheep (or any livestock) on agistment i.e. an agreed price per head per week over a predefined period of time is a straightforward, low cost, grazing agreement that provides the landowner with an additional income stream while retaining flexibility on how these e.g. sheep are used as a grazing management tool on the farm.

The incoming grazier has limited security but benefits from e.g. additional grazing as required, higher quality grazing or clean grazing. Actual grazing numbers need to remain flexible to adjust for weather conditions and grass availability change through a season.

Where the incoming grazier does not have exclusive access to the fields, greater trust is required in the farmer to ensure livestock are not restricted to poor pasture (without prior knowledge) or performance is not unacceptably compromised through excessive overall stocking.

Responsibility remains with the livestock keeper /owner for cross-compliance purposes.

Similar to any agreement, although possibly of greater risk within a fluid agistment based arrangement, movement of livestock will result in livestock standstill on the receiving holding under biosecurity cross-compliance rules unless there is a functioning Scottish Government RPID approved livestock separation agreement in place. This is true whether it is exclusive access to grazing or shared, see below –

www.gov.scot/Topics/farmingrural/Agriculture/animal-welfare/Diseases/MovementRestrictions/ApplicationNotesHTML.

ALSO SEE JOINT VENTURE FARMING GUIDANCE NOTE:

New Entrants to Farming Programme

There is a network of new entrants across the country at various stages of developing their businesses. You can join in:

- www.facebook.com/NewEntrants

- www.fas.scot/new-entrants/

- Regional workshops

For more info contact Kirsten Williams, Consultant, SAC Consulting, Clifton Road, Turriff, 01888 563333, Kirsten.Williams@sac.co.uk

There are useful free resources on this website too:

- Case studies—learning from the experiences of other new entrants.

- Guidance notes—benefit from advice tailored to assist new entrants to farming.

- Also see www.gov.scot/Topics/farmingrural/Agriculture/NewEntrantsToFarming

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service