Drones and Remote Sensing for Biodiversity Monitoring and Land Management

9 December 2025The use of drones, or UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles), for monitoring of biodiversity in Scotland is growing rapidly and is likely to become a standard part of the toolkit for many land managers seeking accurate, efficient and repeatable ways to establish baselines and measure change in habitats and species.

This article provides an overview of the applications of this technology and an understanding of the equipment and techniques that can be used. This will help interested land managers decide whether this is something that they could invest in themselves or whether it will be better to use a professional drone survey service.

The benefits for land managers

As government policy puts greater emphasis on delivering environmental benefits from farming, and private finance starts to find its way into emerging markets for natural capital, it will become increasingly important that land managers can reliably assess the baseline condition of biodiversity on their land and accurately measure changes over time. Carbon credits for woodland creation and peatland restoration are already subject to robust verification measures and metrics are likely to become an important part of future biodiversity credits, as is already the case for Biodiversity Net Gain in England.

This is where drone-based remote sensing can play a role to help land-managers and ecologists to monitor, map and measure habitats and species quickly, and at scale.

What types of remote sensing can be carried out using a drone?

Drones can be fitted with different types of sensor/camera depending on the type of measurement required. For ecological or land management purposes, the most common types include:

- RGB (Red-Green-Blue) cameras for standard visible light imagery.

- Thermal sensors for detecting infra-red radiation (emitted heat).

- Multispectral sensors for capturing reflectance in discrete wavelength bands, including those beyond the visible spectrum such as near-infrared (NIR) or red edge.

- LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) measures reflected laser pulses and can be used to create detailed 3D models of vegetation and land surfaces.

Normal visible light cameras (RGB) are the most easily accessible type of remote sensing as they are fitted to most entry-level consumer drones, costing up to around £1000, whereas the other types of sensor are only found on much more expensive drones, typically costing £4000-£5000 or more, and are more likely to be the preserve of professional operators.

However, the good news is that even a basic multirotor drone with a good-quality camera can deliver useful results, including:

- High-resolution imagery of vegetation cover for habitat mapping

- Rapid access to remote or rough terrain that would be difficult to survey on foot

- Repeat flights to track change over time

For example: you could fly a 20-minute mission over a degraded peatland to map bare peat, and erosion gullies. In woodland you could survey the canopy edge to identify gaps or regeneration, or you could map the spread of invasive species such as rhododendron or bracken.

While it is possible to carry out some of these tasks using satellite and aerial imagery available online, this may not be completely up to date or may not provide enough detail at the farm scale to accurately identify vegetation and measure to the required standard.

It is important to remember that there are strict regulations regarding the use of drones and to ensure that anyone operating a drone on your land complies with all rules and any requirements for registration, training and insurance. The basic requirements are summarised at the end of this article.

Getting the most from standard drone imagery

While basic photographic images from an entry-level drone can provide a useful overview and information about your land, maximising their value will usually require some sort of post-processing using specialised software. This is particularly the case if accurate mapping and measuring of features is required.

Examples of this type of image-processing include:

- Stitching together overlapping images and removing distortions (orthorectification) so that images can be accurately overlaid on a map in a Geographical Information System (GIS)

- Using overlapping 2D images to create an estimate of their 3D structure using a process called Structure from Motion, which works in a similar way to stereoscopic imaging.

Both processes will require photogrammetry software and while Structure from Motion does not provide such a detailed 3D model as LiDAR, it can provide a basic measure of the volume of vegetation on a site.

Moving beyond this stage, artificial intelligence models can also be trained to distinguish certain vegetation types based on colour, texture and shape in standard images, and use this to automatically measure the extent of things like bare peat or invasive plants.

While this type of analysis may require help from someone proficient in the use of the appropriate software, it can provide useful data without the need for professional drones.

Understanding advanced remote sensing

Stepping up from basic drone surveys to the use of more advanced technology is likely to require the use of professional service providers due to the cost of more specialist equipment and the training required to use it. However, it is still useful to understand the technology available and the potential applications.

Thermal imaging

This can be used for surveying wildlife such as deer or ground-nesting birds. Mounting a thermal imaging sensor on a drone allows the same thing to be done more quickly over larger areas and in wooded areas where ground-based observation is not possible. We take a deeper look at the potential of hand-held imagery in a separate article.

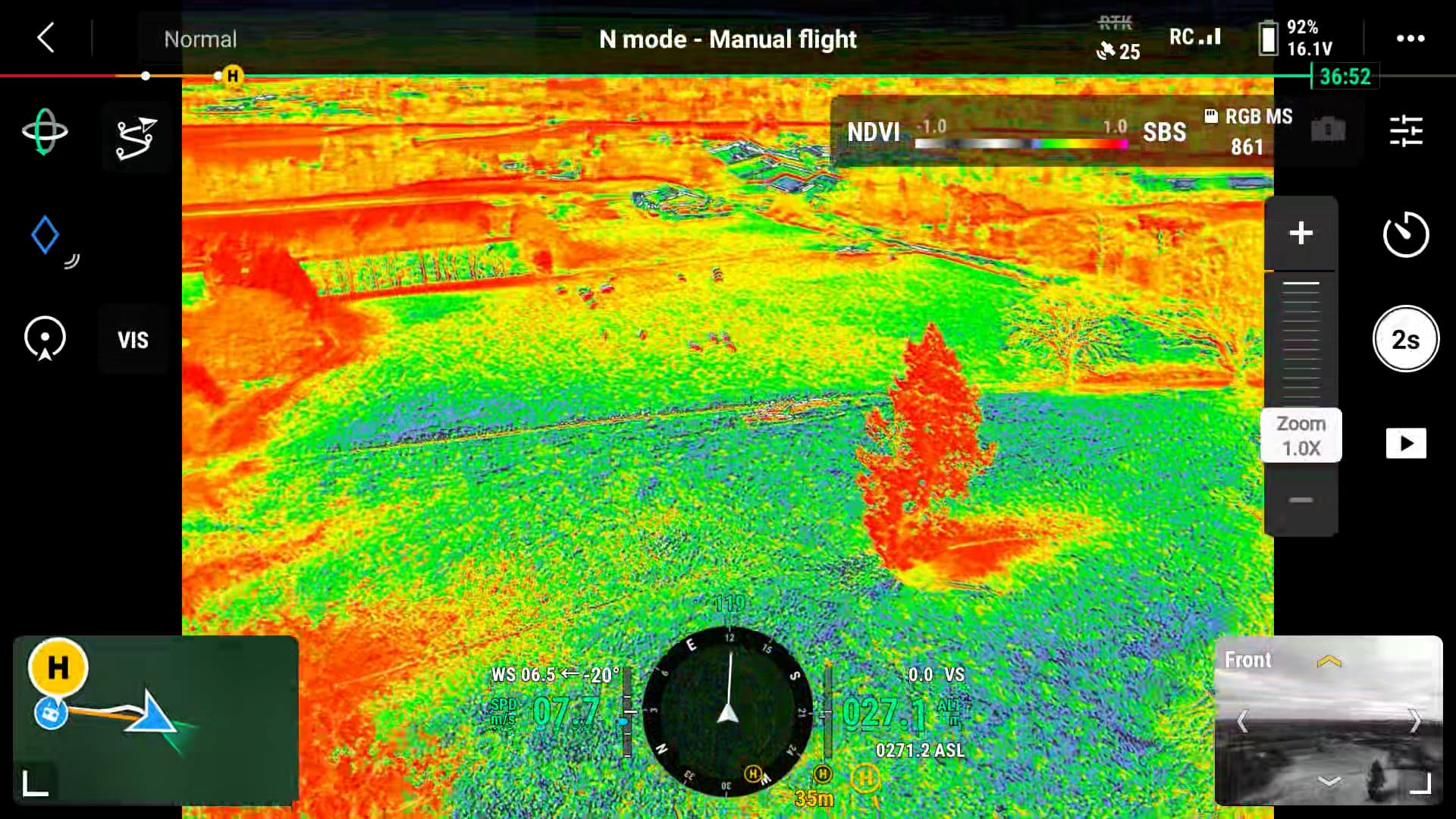

Multispectral Surveys

These bring a depth of information and detail that simply isn’t possible using standard imagery. These sensors measure light in discrete bands beyond the visible spectrum can be used to calculate vegetation indices, which can be used to provide information on vegetation health, biomass, stress and species composition.

- NDVI (Normalised Difference Vegetation Index) is the most widely used vegetation index and is based on near-infrared (NIR) and red light. Stressed or sparse vegetation reflects less NIR and more red light and results in a low NDVI.

- NDRE (Normalised Difference Red Edge Index) is similar to NDVI but uses the Red Edge band instead of the Red band. The Red Edge band sits between Red and NIR wavelengths. It is more sensitive than NDVI in dense vegetation and can detect more subtle stress.

- OSAVI (Optimised Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index) is similar to NDVI but is more effecting in sparse or lower growing vegetation such as bare peat, machair and dune vegetation or areas where bracken has been removed.

In Scotland these indices can be used to:

- Detect early stress in native woodland regeneration.

- Distinguish vigorous, mature and declining heather growth.

- Map bare peat and sphagnum recovery across a peatland restoration site.

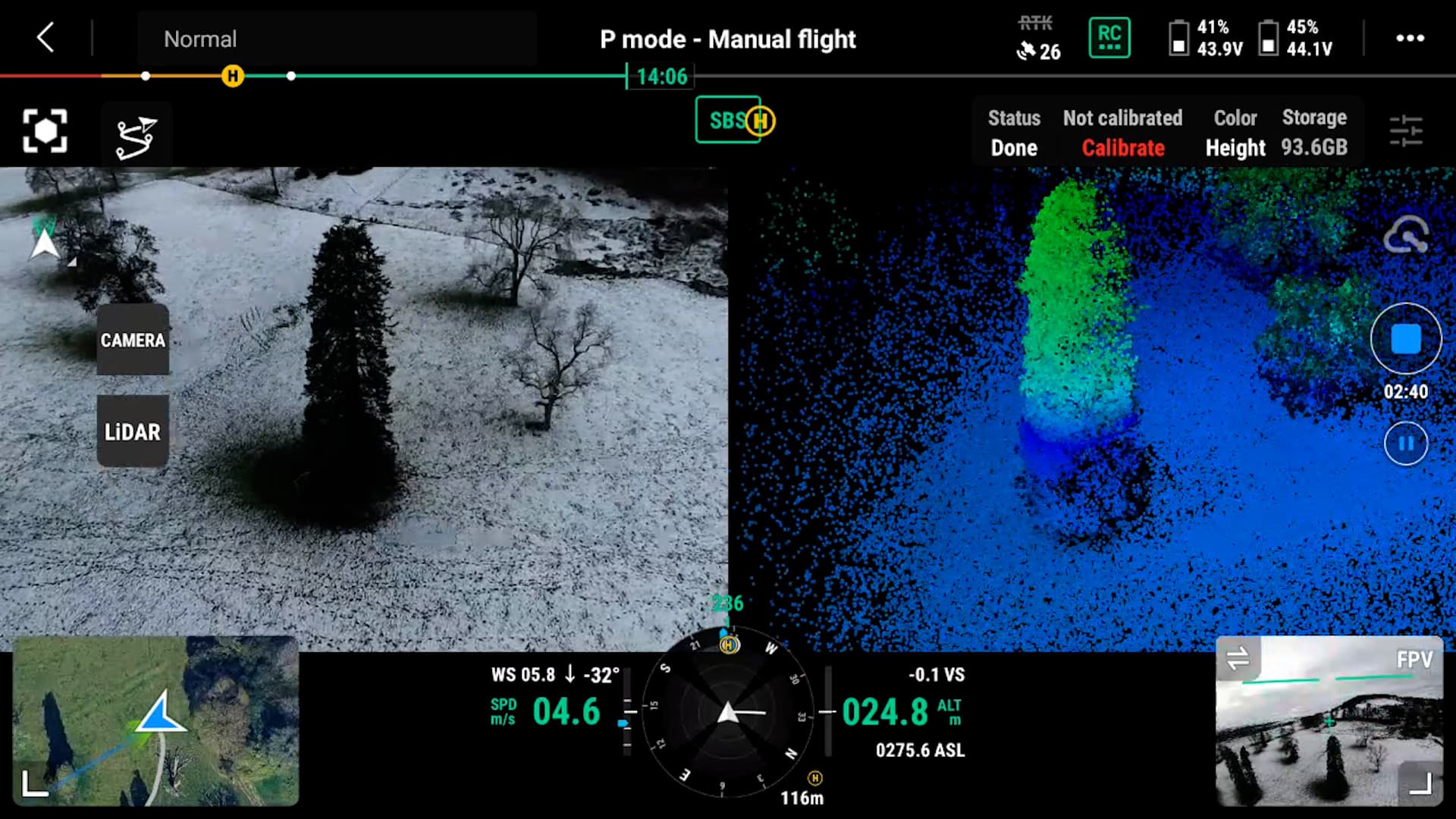

LiDAR

These sensors measure the time taken for laser pulses to be reflected off the surface below, penetrating the vegetation canopy, capturing tree height, shrub layers, and terrain under vegetation and produces a detailed three-dimensional model of both terrain and vegetation structure. This can be very useful for creating detailed hydrological models for peatland or floodplain restoration sites. For habitats like native woodlands, LiDAR data allows professional surveyors to quantify biomass, canopy complexity and structural habitat condition. This can be particularly useful for accurate measurement of carbon stocks or the spread of invasive plants such as rhododendron,and is far more detailed than photogrammetry from standard photographs.

Summary

Drone-based remote sensing offers a scalable, efficient and increasingly accessible way to monitor Scotland’s habitats and safeguard biodiversity. Whether it’s basic survey work using entry-level drones or more advanced analysis using a professional drone operator, drones and remote sensing are set to become a vital part of the toolkit for many land-managers working for nature recovery in Scotland.

Paul Chapman, SAC Consulting

Related Resources

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service