Grazing for Profit and Biodiversity: Adaptive Grazing

15 December 2023Three Rules of Adaptive Stewardship Grazing

Adaptive stewardship grazing is a multi-paddock grazing strategy based on short duration high stock density grazing followed by rest periods targeting complete root system recovery between grazings. It is also known as adaptive grazing, adaptive multi-paddock grazing and regenerative grazing.

The approach is adaptive not prescriptive, meaning plans should be made (e.g. rotational grazing plans) but then adapted based on observations and changes in goals, objectives and environmental conditions. It allows the grazier to work on multiple goals simultaneously for example animal performance, soil health and plant species diversity.

Understanding Ag in the US have developed the three rules of adaptive stewardship which provide a set of principles used to influence adaptive grazing management.

Three rules of adaptive stewardship grazing are the:

- Rule of Compounding

- Rule of Diversity

- Rule of Disruption

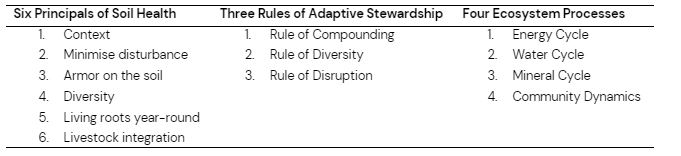

This forms part of what Understanding Ag have coined the 6-3-4™ approach which covers the basic principles and rules that facilitate successful application and implementation of regenerative agriculture. These are:

For more information: The 6-3-4TM Explained - Understanding Ag

Rule of Compounding

The Rule of Compounding follows the concept that every management decision or practice applied creates a series of compounding and cascading effects, which can be positive or negative.

One example is the use of herbicides. Whilst killing a specific ‘weed’, this also sets off a series of cascading negative effects as beneficial species such as clovers and herbs are also killed off alongside microbial populations specific to certain plants. The result being reduced diversity, sward productivity, resilience, and animal performance. Likewise grazing management can lead to positive or negative impacts on plant species diversity with compounding effects.

Daily observations allow the grazier to determine what the compounding effects are and adjust management if necessary. Over time the grazier will develop a keen sense of intuition to facilitate better management decisions towards positive compounding effects. Observations include animal grazing behaviour, which plants are being selectively grazed, pasture growth and recovery after grazing, grazing residuals, earthworm activity, soil health parameters and insect populations.

For more information including discussion on epigenetics see Adaptive Grazing Rules - Part 1 - Understanding Ag.

Rule of Diversity

The Rule of Diversity is to follow the trend of nature to foster highly diverse ecosystems, not monoculture systems. Diversity refers to soil microbial life, plant diversity, insects and wildlife as well as livestock.

This is on the understanding that monoculture/limited diversity in crops or pasture negatively impacts ecosystem diversity and encourages negative compounding and epigenetic effects.

Highly diverse pastures meanwhile, including an array of grasses, legumes and herbs bring cascading positive effects. Herbs for example can bring soil health (root exudates for wider microbial diversity), drought resilience and livestock benefits with beneficial anthelmintic properties, strong nutritional values and mineral balances.

The Rule of Disruption

The Rule of Disruption is based on the understanding that nature is extremely resilient and can recover well from challenges which in fact can often be beneficial to soil health, productivity and diversity.

Grazing which follows a rigid system (e.g. a set paddock grazing plan) will have poor resilience because it hinders diversity and disruption which leads to negative compounding effects. Employing similar practices year on year mean soil microbes, plants and animals become accustomed to the same practice and do not gain resilience and an ability to adapt.

Allen Williams of Understanding Ag uses the example of an athlete. If an athlete does the same exercise routine (intensity, duration) every day they will eventually cease to improve and stagnate. To improve they must alter their routine on a regular basis to challenge their body and mind. Similarly, it is only in this way that microbes, plants and livestock will become more resilient. An example of this would be moving from a set stocked to prescriptive rotational grazing system. We initially see significant benefits and progress, but this will stagnate with no further progress unless disruption is applied.

The following are examples - discussed in more detail in Adaptive Grazing Rules - Part 2 - Understanding Ag - of how planned disruptions can be employed to give pasture/paddock disruptions on an annual basis to prevent stagnation:

1. Alter stock densities.

2. Alter paddock configuration and direction.

3. Alter time of rotations through paddocks.

4. Alter season/month of first/last grazing in each paddock.

5. Alter grazing entry and exit heights.

6. Alter livestock species order.

7. Alter rest period in rotation.

8. Planned burns (practised in the US).

9. Bale grazing.

10. Combination of single disruptions.

What does this mean in a UK context?

In arid and brittle environments, set stocking can lead to over grazing, bare ground, deteriorating soil health and biodiversity and eventually desertification. Adaptive multi-paddock/holistic grazing with short duration high density grazing followed by a period of rest and recovery has been found to reverse this promoting pasture productivity, species diversity and soil health.

In temperate climates, such as the UK, however, set stocking on grass-based pasture doesn’t lead to issues with bare ground and can achieve high pasture yields. That said, conventional UK grazing systems based on set stocking or rotational grazing systems using the 3-leaf rule often have low species diversity and demonstrate poor resilience to adverse weather such as droughts.

Our systems are generally based on prescriptive grazing strategies, the same paddocks grazed in the same order each year with short rest periods and the only adaption to the rotation being to take out a paddock out for silage to maintain pasture in a leafy state. This follows the three rules of adaptive stewardship poorly, often with low species diversity, negative compounding effects and no disruption.

Whilst many will be reluctant to move to high stock density grazing on daily (or more) shifts and long rest periods due to risk of compromising feed quality and individual stock performance, there is still value in many of the principals of adaptive stewardship grazing on more conventional grazing systems. The key being adapting grazing management based on observations. Herbals leys, characterised by often poor persistency, provide a good example of this:

- The value of diversity through herbal leys is well documented with research showing clear benefits to livestock performance and health, pasture yields without synthetic N and benefits to soil health.

- Negative cascading and compounding effects are demonstrated in almost all sown herbal ley management where overgrazing (through set stocked or rotations with insufficient rest and selective grazing behaviour) leads to often rapid decline in species diversity with loss of herbs and most legumes apart from white clover in 2-5 years.

- Always grazing at the same target entry and residual heights only benefits specific plant and leads to diminishing results with a narrowing of plant species diversity, with this comes lower microbial, insect and bird species diversity.

- These swards require a grazing strategy that is adapted by observation and understanding that many of these species (plantain, chicory, red clover, bird foot-trefoil) require a longer rest period between grazings compared to grass to allow full root system recovery. Doing so can lead to positive compounding effects with better persistency of herbs and legumes.

- Planned disruptions can yield positive effects for example altering stock density by moving to daily shifts (greater kgLW/ha in particular paddock) or increasing residual can be beneficial in promoting persistency as they reduce selective grazing on particular species and over grazing.

- Another planned disruption that has shown very positive impacts is altering the rest period with a long summer rest period in periodic years to allow flowering followed by sufficient time to set viable seed, this can lead to self-regenerating pastures with seedlings of plants such as red clover and plantain observed in the following case study - FAS Grazing for Profit and Biodiversity: Muti-Species Swards

Author:

Daniel Stout, SAC Consulting Sheep and Grassland Specialist

More from the series:

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service