Promoting Wildfire Resilience in Woodlands – (FWN36 Spring 2021)

20 May 2021With spring underway, we are moving into the period when the risk of wildfires is generally highest. Here we provide an overview of the risk of wildfire in woodlands, how to plan for resilience and where to go to find more information and advice about helping to prevent wildfire.

Fire is a natural process that can have beneficial effects in some ecosystems. Wildfires may start naturally but the majority are linked to human activity and can be started by something as simple as a discarded cigarette. Most are small incidents but hot and dry weather, wind, and a build-up of dry or dead vegetation all increase the risk of spread. Some may escalate to major incidents that can have detrimental human and environmental impacts. Although wildfires in forests and woodlands make up a relatively small proportion of all wildfire incidents in the UK, their impacts can be large, costly to society and extremely dangerous.

The impacts of wildfires

As well as potentially endangering lives and biodiversity, wildfire can damage property and national infrastructure like transport networks and power lines. Economic impacts include losses to forestry businesses and the wood processing sector, as well as businesses linked with forestry, such as tourism or recreation enterprises.

The potential for wildfire is also a particularly important consideration in the context of climate change. Fire can result in the uncontrolled release of carbon from the entire forest ecosystem. This includes carbon stored above ground in the tree itself, deadwood and leaf litter, as well as below ground within peat soils.

A changing climate

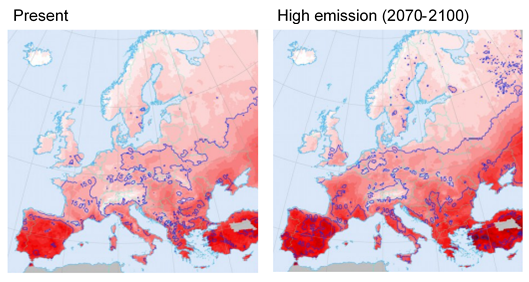

Projections indicate that wildfire risk will rise over the coming decades across Europe (see Figure 1). While the risk level is predicted to remain relatively low in Scotland, there are a number of factors that could have an impact on this, such as rising summer temperatures and increased risk of extreme drought events. Increasing production of vegetation during warmer and wetter winters could create higher fuel loads, also influenced by changes in land management practices. Other events such as pest and disease outbreaks and windthrow have the potential to increase fuel loads in the form of deadwood. The scientific evidence base on wildfire is constantly evolving and current research is focusing on improving our fire danger rating systems to incorporate local vegetation types and create models for future predictions.

Figure 1. Current and projected future forest fire danger across Europe, the darker colour represents a higher potential for fire (de Rigo et. al., 2017. Forest fire danger extremes in Europe under climate change.)

Wildfire risk

The management of land adjacent to or near woodlands is important in understanding fire risk. For example, open hill ground in close proximity to woodlands will increase the risk of forest fires, because fires often begin in more flammable grassland or moorland and then spread into woodland. Other forested areas at increased risk include: urban edge woodlands; areas with high recreational use e.g. popular barbeque spots; and woodland next to public roads.

Young woodlands (aged 5 to 20 years) and naturally regenerated woodlands are at the greatest risk of fire. Evergreen coniferous species are generally at higher risk than broadleaves. Fire risk can vary throughout the different stages of the forestry cycle, and is influenced by how the woodland is managed. The likelihood of fires is highest at the thicket stage and before first thinning, and is lowest at the post-thin stage. The risk of fire is highest during periods of dry weather in the spring before the growing season starts when the accumulation of dead vegetation, e.g. grass from the previous season, creates a high fuel load.

Planning for resilience

Whilst wildfires cannot always be prevented, good woodland management planning can help reduce the likelihood of wildfires occurring and reduce the potential for spread if a fire starts. The UK Forestry Standard (UKFS) advises that managers should plan for forest resilience using a variety of ages, species and stand structure, whilst considering the risks to the woodland from wind, fire, and pest and disease outbreaks. The UKFS also advises that appropriate contingency plans should be put in place to deal with risks to the woodland, including extreme weather events and fire.

The associated Practice Guide (see Resources) sets out good practice, both planning and operational, for building wildfire resilience into woodland management planning at a landscape scale. This is important to prevent small wildfire incidents escalating into large-scale events. The guidance applies to both new and existing forests and woodlands. It is not intended to be prescriptive and should be applied proportionately to the level of risk of a wildfire occurring in a particular forest or woodland.

Planning to prevent or manage wildfire in woodlands can be improved by selecting appropriate tree species and silvicultural systems, for example maintaining a range of age classes and structures across a woodland. In high-risk areas, vegetation should be managed to prevent build-up of fuel load. Timber and brash left on site after harvesting and thinning may present an increased hazard until they decay. Similarly, diseased, windblown, damaged, dead or dying trees and deadwood can increase the likelihood and severity of wildfires.

| How can you reduce the risk? |

| Key messages for woodland planning: Prioritising high risk areas, manage vegetation to reduce fuel loads e.g. swipe rides and road edges Incorporate fire breaks into forest design, making use of natural features such as water courses. Increase structural diversity by planting a range of species and breaking up single age stands. Ensure good access for firefighting, e.g. avoid creating dead end roads, or install turning points. Keep an up-to-date fire plan with ponds and other water sources shown on maps. Share a copy with Scottish Fire and Rescue Service. |

Resources and further information

Scottish Fire and Rescue Service

Forestry Commission Practice Guide

FISA Guide: FirefightingScottish

Local wildfire groups:

- North Grampian Forest Fire Protection Group

- South Grampian Wildfire Group

- Badenoch and Speyside Wildfire Group

Kerstin Kinnaird MICFor, Land Use & Climate Change Policy Support Officer, Scottish Forestry

This article has been published in the Spring 2021 edition of the Farm Woodland News. Download a copy to access all articles. Subscribe to receive newly published editions via email by using the form here.

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service