Providing a Comfortable Thermal Environment for Calves

30 April 2024Despite the various methods for housing calves (e.g. individual, paired, group, pens, hutches) the basic principles for housing should be the same. The environment should be as clean as possible, dry and free from any draughts at calf height. It should also be well ventilated and provide a comfortable thermal environment for the calf.

What is a ‘comfortable’ thermal environment?

The neonatal calf is born into an environment that has a temperature which is lower than that in-utero. As a homeotherm the calf needs to maintain a constant body temperature, which is achieved through a balance of the amount of heat produced with the amount lost to the environment.

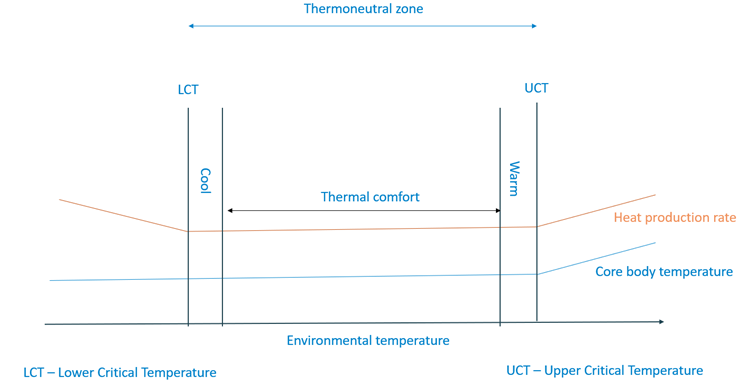

Illustration of thermal zones

The thermal comfort zone is the environmental temperature at which the calf is not motivated to perform any thermoregulatory behaviour, such as huddling with other calves or nesting into the bedding. This is often thought to be between 15 and 25oC. As the environmental temperature starts to warm up, a point referred to as the Upper Critical Temperature (UCT) is reached, estimated to be above 25oC. At such temperatures calves will start to experience heat stress. Although not thought to be much of an issue in Scotland, if we continue to have periods of the year with extreme temperatures, then heat stress is something that we must start to take more seriously.

As environmental temperatures cool down, a point referred to as the Lower Critical Temperature (LCT) is reached. At temperatures leading to the LCT, the calf still won’t require any additional energy to produce heat to maintain warmth, but instead use non-evaporative processes such as behaviours like removing itself from certain environments within the pen if this is possible.

The LCT for a newborn calf is generally in the region of 15oC. However, the LCT is not a static value and is affected by various factors such as breed, age and general weather conditions. The LCT for a newborn Jersey calf is much higher than that of a Holstein calf, generally thought to be around 18-20oC. As calves get older the LCT starts to reduce as it does not need to produce as much heat to maintain its core body temperature. Much of the available literature states that by one month of age, calves will have a LCT of 0oC under ideal circumstances. Draughts (i.e. air speeds in excess of 0.2m/s) can produce a cooling effect on the calf causing the LCT to increase.

Practical adaption strategies

- Bedding – adequate levels of bedding material should be applied to the pen for the calf. In the UK, the predominant bedding material used is straw. To quantify if there are adequate levels of bedding, nesting scores can be carried out. A nesting score of one (when the calf’s legs are entirely visible when lying down) indicates more bedding is needed and a nesting score of three (the calf’s legs are not visible when lying down) indicates that there is sufficient bedding. If straw is in short supply, then the youngest calves should be prioritised, and consider other bedding materials for the older calves and cattle.

- Feeding – during environmental temperatures that are below the LCT, calves need to increase heat production. It is encouraged to increase feeding levels during such periods to allow calves access to more energy in their diet.

- Calf jackets – the use of calf jackets, especially during the winter months of the year, is increasing in popularity. Ensure that clean and dry calf jackets are applied to the calf when it is dry. Again, if running short of a supply of calf jackets, the priority should be for the youngest calves.

well bedded calf (nesting score 3)

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service