Small scale machinery (FWN 30)

26 March 2018Under the Forestry Grant Scheme (FGS) – Harvesting and Processing Grant, certain pieces of machinery suitable for farm scale woodland management and timber processing are available, namely firewood processors, mobile sawmills, forestry trailers and forestry winches.

Often these bits of kit are not economic at the scale of some smaller operations, however, with a grant rate of 40% it could be worth considering. Therefore this piece aims to give an introduction to the choice of equipment and a brief outline of the grant process.

Grant eligibility

The grant is aimed at smaller scale woodland businesses. Eligible business must be considered a “micro enterprise” (fewer than 10 people, annual turnover of less than EUR 2 million) and not produce more than 5,000 tonnes a year. But it is also aimed at the business which will use the equipment enough to justify funding from the public purse. Therefore you must use the primary processing or harvesting machinery purchased for at least 500 hours per year. Information on the grant can be found from Rural Payments

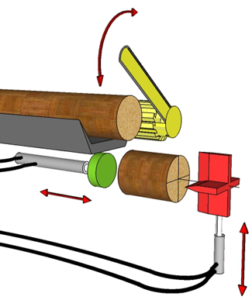

These range from simple splitters to fully automated processors. Under the grant scheme these are considered primary processing equipment, therefore will need to be used 500 hours a year, which is very likely to rule out all the less frequently used equipment such as splitters. We will, therefore, take a look at full processors which both cross-cut and split the firewood. However as these machines will produce 1-2 dry tonnes of firewood an hour, you need to have a sizeable firewood market to be eligible for the grant.

Firewood processors of all designs work best on straight, unbranched long length timber, therefore these expensive machines are less likely to justify their price when used on short uneven timber i.e. timber that is not from plantation forestry.

How to Cut the Log – Chainsaw, Circular Saw or Knife?

The most common types of processors have either a chainsaw blade or circular saw to cross cut the wood, also less commonly guillotines or knives are used – each has its own advantages;

- Chainsaw blade – can be maintained by the operator, forgiving on stones and metal, can do very large diameter wood, daily sharpening, slower cutting, complex hydraulics, high kerf (width of cut) and hence more wastage.

- Circular saw – low kerf, faster cutting, only need to sharpen every few months to a year, most small scale machines are limited to less than 40cm diameter timber, stones and metal are very expensive on the blade, will usually need to send away blades for maintenance, most models need to wait for saw to stop before getting access to jammed logs (which they will do) and therefore can be slower in some circumstances.

- Guillotine or knives – very low maintenance, zero kerf, very high output, less prone to jamming, only for small diameter timber less than 20cm, expensive, produce rougher looking logs, need consistent smaller diameter wood.

Once the timber has been cross-cut, it will then need to be split. Conventionally this is done with a hydraulic ram pushing the cut log against a splitting wedge (knife). The knife can have a single blade which will split the log in two (2-way), 2 blades in a cross which will split the log in four (4 way) and multiple blades (6, 8, 10-way etc.) for more powerful processors. The larger the diameter of timber the machine handles, the more blades the knife will need to keep the firewood at an acceptable diameter. However, as soon as there is more than one log diameter, the height of the knife needs to be adjusted to ensure it splits from the centre of the log. For reasonably consistent diameter timber this is not too much of a problem, the height is adjusted once to match the timber, if not then every time the log diameter changes, adjustments will be required. On basic machines this is done manually by lifting and locking the knife, more sophisticated machines have a hydraulic ram to quickly adjust the height as the log is fed onto the knife.

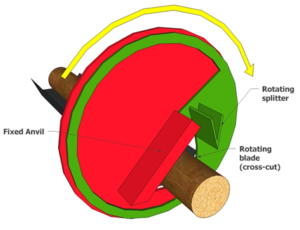

Guillotine processors such as the Bilke S3 work differently, the guillotine which does the cross-cutting is actually a rotating blade which incorporates the splitting knife (see figure 2).

In order to get the most out of any processor, and to get it anywhere near its potential output, a log deck is essential. The log deck holds a stack of timber and allows it to be fed

onto the processor quickly, they range from simple trestles which require the operator to roll the logs into the feed deck, to fully automated hydraulic feeders which integrate with the processor. Log decks are eligible for grant funding.

Whilst kindling machines are in principle eligible for the grant, the 500 hour minimum usage would mean that with even the smaller machines you would need to sell 30,000 – 50,000 nets a year. Therefore only realistically in the range of kindling wholesalers.

Small scale sawmills / peeler-pointers

Small scale sawmills are counted as primary processing equipment and therefore need to be used for at least 500 hours a year – likely eliminating smaller scale kit such as chainsaw mills, leaving a choice between a circular saw or bandsaw mills. The ability to move the mill around to take it to a customer’s site does allow you to diversify into rental, and most types of saw have mobile versions too. Basically circular sawmills are cheaper, bandsaws can cope with bigger logs, cut slightly straighter and have less kerf.

- Circular swing blade saw mills – such as the Lucas mill, these are very portable by having a relatively small circular saw, which moves through 90 degrees rather than having to turn the log. This saves on all the heavy equipment required to rotate a large log. Typically these mills can only dimension timber to about 6-10 inches.

- Circular sawmill – such as the Liamet mills, not as portable but usually larger cutting dimensions than swing blade types.

- Bandsaw – arguably the most common type of small scale sawmill due to the ability to take very large high value logs with the minimum wastage.

More information on small scale sawmilling is available from the Association of Scottish Hardwood Sawmillers (ASHS)

- Peeler pointers – such as those by Neuhauser and Posch for producing round fence posts. Whilst not specifically named in the grant guidance, it is likely that peeler-pointers would be eligible in principle, but with

production at about 50-100 posts an hour, the 500-hour utilisation rule of the grant would require production sufficient for 5-10 miles of fencing, making it suitable only for wholesalers or fencing contractors.

Peeler pointers are especially useful for using the smaller 4-6 inch diameter timber, which is very slow when put through firewood processors. These are especially suitable if you have access to large amounts of pine, as pine takes preservative treatments best. It is important to remember that all softwood species need to be treated before use – most sawmills offer this service, but check before buying a peeler pointer.

Peeling is done by a worm drive rotating the post along a grinding disc. the only significant choice when it comes to peeler-pointers is whether to have a circular saw on it to do the pointing rather than using the grinding disc. The circular saw does give the option of producing a half-round post by rip-sawing them in half.

Forestry Winches

One of the most useful tools in the wood is a forestry winch on a tractor suitably adapted for forestry. It can fetch timber from un-driveable places, skid (dragging timber longer distances behind a moving tractor) timber to a point where a lorry or trailer can get it, aid in directional felling of trees, get the tractor out when it’s stuck and some can even act as a mini skyline. The 500 hours rule means this is only for forestry contractors working in the woods 1-2 days a week or hauling out about 1,500 tonnes a year.

The choices when it comes to winches are as follows;

- Pull capacity (tonnes) For skidding purposes there are few tractors, capable of working in the woods, large enough to skid much more than a couple of tonnes of timber, therefore one would possibly think a 2-3 tonne winch would be fine. However a 2 tonne winch can’t skid 2 tonnes of timber, the drag is too great. Depending on ground conditions and the state of the timber, typically a winch can skid about half its pull capacity, therefore a 4 tonne winch should be enough. In reality most woodland contractors’ winches are well over 6.5 tonnes.

- Clutch/brake control to control the winching operation (stopping and starting) a clutch is used, this can be engaged manually on a lever via a rope (manual control) or hydraulically via an electric actuator (electrohydraulic control).The brake is usually either a ratchet type cog or a belt/disk brake, either of which can be manually or electrohydraulically controlled. Electrohydraulic control allows for more sensitive control of the clutch. With the brake type the ratchet is either on or off; there is no capacity for slip therefore it is aggressive and harsh, but robust. Disk/belt/band brakes have less aggressive, more forgiving braking. Hydraulic control also allows for wireless remote control, which can be very useful for one person operation.

- Hydraulically assisted spooling out. As standard on most winches you simply disengage the clutch and brake, then walk the line out to the tree, sounds simple enough, but after doing this all day it can get very tiring. Therefore this could be a wise option for high usage.

- Number of drums. There are winches available with two independent drums, whilst these are very expensive they do have a number of advantages. It is possible to run two dragging operations side by side (one line being hauled out and connected, the other hauling in), can collect two loads on the skidding route, and you have massive puling power when required if both drums used together. Two drums also allow you to set up a mini-skyline system (up to about 150m) known as the “Highlead System”

Forestry trailers

For moving larger quantities of timber in the woods one needs to look at forestry trailers with forestry loader/grab. They are normally sized to match the timber, tractor and likely terrain they are to be used in. It is unlikely that a “15-tonne” trailer will be able to get very far in a wet hillside woodland when fully laden with hardwood.

- Carrying capacity. It should be noted that most trailers do not actually fit their rated load capacity with softwoods. The capacity of the trailer is usually limited by the terrain and ground conditions. If predominantly working on firm, relatively level woodland with a good brash covering, the larger 12-15 tonne trailers may suit, but generally, a 10 tonne trailer would be a useful all-rounder for most larger operations.

- Driven wheels. Most trailers over 6-tonne capacity have the option for the trailer wheels to be driven, most commonly via a “drive” wheel which grips the tyres (see figure 5). A less common option is full hydraulic hubs which give a significant amount of extra drive. In wet woodlands driven wheels are almost essential.

- Steering drawbar. A steering drawbar which is hydraulically operated greatly increase the trailer’s ability to “track” in the same tyre tracks as the tractor, and therefore reduce the risk of accidentally scrapping trees.

- Loader capacity/reach. The most difficult choice for any forestry trailer is the loader selection. As very general rule hardwoods require higher lift capacity, with shorter reach loaders; softwoods can be handled by longer reach loaders (with lift capacity compromised). However, for larger trailers anything less than 7m reach and maximum lift capacity of 1.5 tonnes will compromise the productivity of the trailer.

Training

It should be pointed out that there are certain conditions relating to the grant that could be important when considering the financial case – specifically those relating to training. It is a requirement that the applicant should have training qualifications on the grant-funded equipment. For basic equipment like firewood processors, peeler pointers, small sawmills, it could be a simple certificate of competence from a 1-day training course. However for harvesting and forwarding equipment such as winches and forestry trailers, full Forestry Machine Operators (FMO) certificates are expected, and the not inconsiderable costs of these (which cannot be covered by the grant) should be taken into account.

John Farquhar, SAC Consulting

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service