Timber quality – A product of it’s environment (FWN31)

30 September 2018The importance of managing your woodland to maximise saw log volume is something that cannot be stressed enough.

With biomass prices the strongest they have been in recent years there are fewer and fewer reasons to leave woodland un-managed. Much of the value of the timber in your woodland historically was dependent on your location in relation to markets (i.e. haulage distance). In the event that you were isolated from larger markets the value of your timber would be impacted. Now it may be possible to negotiate sales directly with neighbours who use woodchip boilers, saving on haulage costs to the point that lower value chip material could have a net return price similar to other higher-value products which have to travel further to market. (Net return is the net price offered for the purchase of the produce after harvesting and haulage cost have been deducted).

First thinnings are now, therefore, more likely to cover their costs or to generate a small income. A first thinning is where approximately 20% of the crop is removed by the creation of ‘racks’; these are lines of trees that a harvester will fell through the crop, usually two rows wide, and creating access routes for future thinnings.

Typically only one or two products are cut, the main one being chipwood with perhaps some pallet wood, due to small tree size and a lack of space within the forest for processing trees and for separating different products. It may be possible to cut a short log or fencing posts, but this is dependent on local markets.

There is also an argument to cut chipwood only, the reduced income from timber can be off-set by a reduced working cost from the contractor as the timber can be harvested and extracted more quickly.

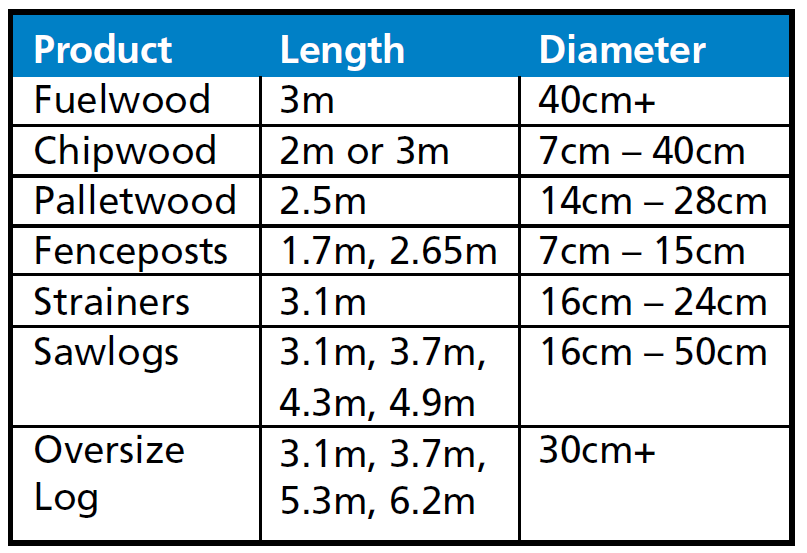

Subsequent thinnings (also known as matrix thinning) are carried out every 5 -10 years following the first thinning, depending on how well the crop is growing. As the remaining stems increase in volume, and the working space is increased (by removal of poorer quality stems) it is possible to cut a wider range of products which leads to an increased return. Having an increased average diameter leads to better options for products (see table below for specifications) to be cut and means the operator can cut higher value products.

Upon clear-felling a well-managed forest the log content should be in excess of 50% of the crop (in some cases over 70%) as all poor quality and small trees have been removed and the trees with best form (straightness, taper, girth along with absence of rot and heavy branching – the exception being edge trees) are all that is left. The production rate of the machine is higher in clearfells compared to thinning which will be reflected in the working rate.

However, a large number of products will lead to an increase in working cost; it is important to bear this in mind as it may be worth cutting fewer products for a better return.

Typical product categories and sizes.

*Other lengths of products may be requested by sawmills, the above are the most common lengths for each product.

In an ideal world the first cut (butt) from each tree felled would be a sawlog. Sawlogs might not be cut for the following reasons:

- Taper – sawmills will not accept a significant taper between each end of the log; it is common to cut a ‘clog’ to remove flared butts and bring the diameter into line with a sawlog, alternatively a length of fuelwood can be cut to achieve the same outcome, although this reduces the length of stem available for cutting a sawlog.

- Branching – for more open-grown trees heavy branching can be an issue as it will mean there are knots in the wood. Sawmills will accept knots up to 2 inches but prefer not to have large amounts of knots.

- Metal – as the butt is the part of the tree most accessible it is possible that metal may be present from fencing (or worse still, tree-houses). If suspected to be present then the first cut could become fuelwood or chipwood – but any mill reserves the right to reject timber containing metal as it can damage equipment.

- Rot – should the tree contain significant rot the length would become chip or fuelwood. There may be signs of rot whilst he crop is standing such as drought crack, a confirmation of the presence of rot is made by the harvesting operator who can see a cross-section of the trunk following felling.

In mature, well-managed crops, it is possible to cut three, or even four, logs from the butt end before the diameter falls into the pallet, or strainer category.

Taper and branching are still a concern for pallet wood and strainers. In the case that either of these are an issue then the stem may be cut into chipwood. Material under 7cm diameter is deemed non-merchantable and is left onsite as a brash mat which provides floatation for machinery in order to reduce ground damage. It is possible to recover this brash material, chip it at the roadside and have lorries collect it from the site, this is dependant on the area, quality of brash and access to the site, to be cost-effective.

Fencing posts can be cut from the top of large trees but branching can often prevent this. More commonly they are cut from younger crops where the average diameter of the trunk falls within the range detailed in the table above.

The information stated in the text and table above is for general guidance. New processes and products are being developed and explored which could lead to new and innovative opportunities.

Douglas Priest, SAC Consulting

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service