Conserving the Corn Bunting in Scotland

22 September 2025Biodiversity conservation is often more effective when implemented across larger areas than a single farm. Collaboration within farmer clusters and with other stakeholders enables farmers to implement measures to enhance biodiversity at a landscape-scale. It can also help foster a sense of community and shared responsibility for the environment.

A multi-year period of partnership working between researchers and groups of farmers have revealed the causes of and potential solutions to Corn Bunting decline in Scotland. Maintaining these partnerships over several years has helped to refine the solutions so that they fit more easily into farming systems and has influenced the development of agri-environment support schemes.

By working together, groups of farmers in areas like the East Neuk of Fife have implemented the necessary measures and reversed the decline of the Corn Bunting, providing a great example of farming delivering real biodiversity gains. In this case study, we look at collaborative efforts to conserve the Corn Bunting in Scotland, which have used the results of targeted research to implement management measures that are now delivering positive results. Populations have stabilised or increased in areas where groups of farmers have worked together to help this bird.

What is the issue?

The Corn Bunting (Emberiza calandra) has been brought close to the brink of extinction in Scotland due to changes in the way that farmland is managed. This nondescript streaky brown seed-eating bird, similar in size and appearance to a skylark, was formerly found throughout all cultivated land in Scotland, from Shetland to Galloway and its distinctive, jangling metallic song would have been a constant feature of the summer.

During the 20th century, the Corn Bunting gradually disappeared from many areas and by the early 21st century there were estimated to be only 800 pairs left in Scotland, concentrated in the north-east lowlands of Aberdeenshire and Moray, with small numbers also surviving in Fife and Angus and a tiny relict Western Isles population in the Uists. This put it at real risk of extinction from the country.

Corn Buntings feed on seeds, particularly large seeds such as cereal grains, and in summer they feed their chicks on large protein-rich insects such as caterpillars. Like many other seed-eating farmland birds, this species has suffered due to the loss of seed-rich stubble fields over the winter, both due to the increase in autumn-sown cereals in southern and eastern Scotland, and the loss of cereal cropping altogether in the north and west.

At the same time, intensification of grassland management and the loss of semi-natural habitats has reduced the availability of large insects during the breeding season.

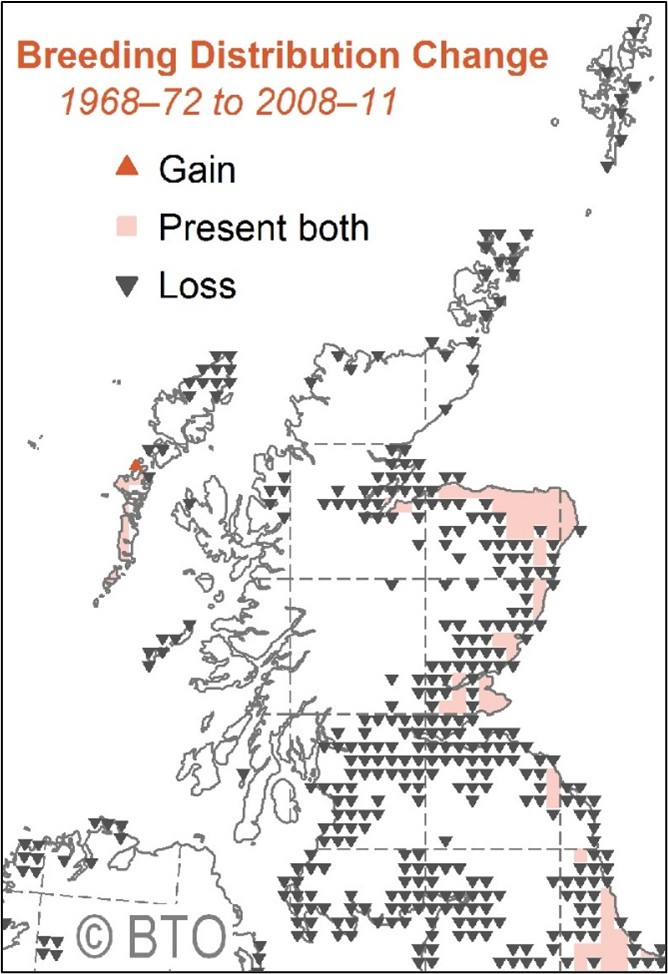

Map showing the loss of Corn Buntings from most of lowland Scotland between 1968 and 2011. Map reproduced from Bird Atlas 2007–11, which is a joint project between, BTO, BirdWatch Ireland and the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club. Map reproduced with permission from the British Trust for Ornithology.

A particular problem unique to the Corn Bunting is that it nests on the ground in dense cover out in the middle of fields and does so quite late in the summer compared to other ground-nesting birds. The first eggs are not laid until late May or June, and nests can be active with second broods into August or even September. Although cereal crops are the most frequently used nesting habitat, they can be quite sparsely vegetated when nesting starts (particularly spring-sown cereals). Grass silage fields typically provide much more attractive dense nesting cover in May and early June and will be preferentially selected for nesting if available. This creates a trap for Corn Buntings as the nests will then be destroyed if silage is mown in mid to late June, as is typical in Scotland.

Late mown silage field used by nesting Corn Buntings in Aberdeenshire

Why does collaboration make sense?

Across their remaining range, the population density of Corn Buntings averages less than 1 territory per km2, although densities of 10-20 territories per km2 can be found in the most favoured areas. With farms in these areas rarely being larger than 2km2, individual farmers can each only support a tiny population of birds. These are vulnerable to the chance effects of bad weather, predation, unintended changes in farm management, and inbreeding, all of which can easily tip very small populations towards local extinction.

To have a sustainable, resilient population of Corn Buntings that will weather short-term ups and downs is likely to require a contiguous area supporting several hundred territories or more. This is only possible if multiple farmers are delivering the management that is needed by this bird across the wider landscape.

In the case of the Corn Bunting, the starting point for collaborative, landscape-scale management was meticulous research into breeding success and the factors that were causing population declines. This was primarily led by scientists from RSPB Scotland working with the support of local farmers. Having identified the most important factors, the research moved on to trialling targeted management interventions to see what could work within current farming systems. By building a solid evidence base, these findings have been incorporated into agri-environment schemes and disseminated to farmers through workshops and events involving SAC Consulting and other local advisors and consultants.

Groups of farmers and estate managers in Aberdeenshire, Angus and Fife have implemented management as part of the Corn Bunting recovery project and these have been highly successful. In the East Neuk of Fife, the population has increased from fewer than 100 territories to more than 400 territories in a period of little more than10 years. In Angus the population has tripled from a critical low of fewer than 20 territories. Such positive responses have not yet been seen in Aberdeenshire and Moray, but there is evidence that targeted interventions have at least stopped the decline there and stabilised the largest remaining population of the species. There have also been recent sightings of Corn Buntings in parts of Aberdeenshire where they had disappeared in previous decades.

What needs to happen?

In Angus and Fife, research indicated that the single most important factor in the historical decline was a lack of seed food over the winter, due to the predominance of winter cereals and more efficient harvesting meaning less spilt grain in the remaining stubble fields. By sowing blocks of wild bird seed crops in suitable open farmland, farmers can provide excellent winter feeding habitats for Corn Buntings and other seed eating birds.

Due to their preference for larger seeds, a special Corn Bunting seed mix has been developed that includes a mix of oats, barley and triticale. These three cereal grains fall to the ground and become available for feeding birds at different stages over the winter, providing a regular food supply throughout the season. Larger blocks of wild bird seed also provide attractive and safe nesting areas for Corn Buntings during the summer and, due to the lack of sprays, provide insect-rich habitats too.

Wild Bird Seed mix for Corn Buntings in Angus

In Aberdeenshire, reversing, rather than just halting, population declines is more challenging. Silage fields in May and early June continue to act as a trap for Corn Buntings, providing the most attractive nesting habitat in many areas, only to be mown before the chicks have fledged. Although payment for a late cut mown grassland option for Corn Buntings has been available under AECS since 2008, the loss of silage quality that comes from leaving cutting until August means that the uptake of this option has not been sufficient to significantly increase the population.

However, recent research by RSPB has provided a new potential solution. Green manure crops are a popular agri-environment scheme option for arable farmers as they build organic matter in the soil and reduce the fertiliser inputs required for the following commercial crop. However, they are currently usually sown in the spring (AECS rules require the stubble from the preceding crop to be retained over the winter before the green manure crop is sown). This means the crop is often not very well grown when Corn Buntings start to nest.

Green manure crop

The research by RSPB Scotland, in collaboration with several Aberdeenshire farmers and Kings Crops (Frontier Agriculture), trialled autumn sown green manure crops based on rye-grass mixed with several types of clover and vetch. This provided nesting cover at least as tall and dense as silage grass in late May and remained tall and dense throughout the summer, allowing second nesting attempts. Corn Buntings preferentially selected the autumn-sown green manure crops for nesting and had high nest survival rates.

In the Western Isles, the tiny, isolated population of Corn Buntings is dependent on the continuation of cereal cropping in the machair, but the trend towards harvesting crops for arable silage has reduced the availability of grain. Wild bird seed mixes therefore have the potential to benefit the species here too.

In all areas, insect-rich habitat is required during the summer to provide food for the chicks. This can be provided by natural species-rich grassland, such as the machair grassland in the Western Isles, but in the more intensively farmed east of Scotland, can be created in the form of species-rich field margins and low-intensity grassland.

Cropped machair in the Western Isles

Within all parts of the Corn Bunting’s remaining range:

- Grain-rich habitat such as a suitable wild bird seed mix should be established, with a target of at least 2 hectares per 100 hectares of farmland.

- Wild bird seed should be established as large blocks, rather than strips, and should be located away from woodland in more open farmland.

- Insect-rich habitats such as species-rich grasslands or diverse field margins should be created or managed to provide sufficient food for chicks.

In north-east Scotland:

- Corn Bunting Mown Grassland and autumn sown green manure crops should be used to provide safe nesting habitats, ideally targeted on and near fields used by Corn Buntings currently.

Implementing these measures, which could be supported through the Ecological Focus Area requirements of BPS greening, or through Agri-environment Climate Schemes (AECS) will reverse the decline of this species and allow it to return to areas from which it has been lost.

Paul Chapman, SAC Consulting

Related Links

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service